Author:

Supply Chain Indonesia & Indonesian Business Council

19 May 2025

This article is in collaboration with:

The administration of President Prabowo has outlined a set of “herculean missions,” setting forth ambitious targets such as the downstreaming of 28 key commodities, accelerating manufacturing growth to 5.5–6.1% by 2025, and raising the manufacturing sector’s contribution to GDP to 19.6%. Achieving these goals will depend not only on effective investment and industrial policies but also on the strength of Indonesia’s logistics sector. As the backbone of supply chains, logistics plays a pivotal dual role: ensuring the smooth inflow of raw materials into production hubs and facilitating the distribution of finished, value-added goods to both domestic and international markets. In this context, a modern, resilient, and integrated logistics system is not merely supportive infrastructure—it is a strategic enabler of national economic transformation.

Despite the ambitions, the path forward is fraught with external headwinds. Global trade is entering a volatile phase, marked by escalating geopolitical tensions and a resurgence of protectionism. Former President Donald Trump has signaled a return to trade-war policies, including the reimposition of steep reciprocal tariffs, reigniting fears of global supply chain fragmentation, higher import costs, and widespread trade disruptions. These shifts pose significant challenges for emerging economies like Indonesia—particularly considering the 32% tariffs recently imposed by the United States, Indonesia’s second-largest commodities importer.

Such trade measures are expected to reroute global shipping lanes, increase the cost of imported inputs, and trigger bottlenecks across international logistics networks. For Indonesia, these developments threaten to undermine competitiveness and impede efforts to modernize the economy.

What will be at stake?

The overall outlook on the impact of the tariffs is challenging. Critical labor-intensive sectors such as electronics, furniture, apparel, and rubber products would be most affected, threatening Indonesia’s overall trade position and economic resilience. In response, the government has floated the ideas of loosening Domestic Component Level (TKDN) regulations to be more pragmatic, and for the elimination of import quotas to ensure the availability of goods that are vital for Indonesian citizens. Although many stakeholders have welcomed the shift towards creating a more conducive environment for business operations and investment, others have expressed concerns that the liberalization of long-standing protectionist measures might weaken domestic industries.

Beyond the direct impact on specific industries, the tariffs further jeopardize Indonesia’s market access and competitiveness, especially as the country has lost its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) status with the United States in late 2020. As a result, Indonesia’s goods are less price-competitive in the American market. Restoring this status is a key diplomatic goal, but one that is difficult in the current climate of the trade war. There are macroeconomic risks at stake, including pressures on the Indonesian balance of trade and foreign exchange reserves if export revenues fall significantly. Furthermore, Indonesia must carefully manage its relationship with major partners like China to thread between becoming a dumping ground for redirected goods while attracting foreign investment and deepening strategic investment.

In practical terms, these challenges could slow down the distribution of key commodities, inflate operational costs for manufacturers and exporters, and ultimately delay national economic targets. If left unaddressed, these disruptions may compromise the competitiveness of Indonesia’s downstream industries and its ability to increase export value, particularly as the country pushes for greater industrialization and processing of natural resources. The potential loss includes decreased investor confidence, missed opportunities in global trade, and weakened supply chain reliability—especially damaging at a time when Prabowo’s administration must show rapid progress.

Logistics Development Strategy

Indonesia’s internal logistics landscape is still evolving. While infrastructure development has progressed in recent years, the sector remains fragmented across ministries, regions, and institutions. Outdated regulatory frameworks—such as Presidential Regulation No. 26/2012 on the National Logistics System Blueprint—no longer reflect the realities of current trade disruptions or the technological capabilities now available.

Efforts at reforming Indonesia’s logistics market have demonstrated lackluster results. Other than Presidential Regulation No. 26/2012, Economic Policy Package (PKE) Phase 15 in 2017 aimed to develop the competitiveness of the logistics industry. It was followed by Presidential Instruction No. 5/2020 regarding the National Logistics Ecosystem (NLE), which aimed to simplify the information ecosystem between vendors through digitalization. While the NLE was able to decrease item dwelling times to 2,52 days–past the target of 2,9 days, logistics price levels in Indonesia still remain at around 14%, compared to the 9-12% benchmarks of other countries pointed out by then-President Joko Widodo. Furthermore, logistics development has traditionally followed a “ship follows the trade” model, which is reactive rather than proactive. This mindset hinders Indonesia’s ability to use logistics as a tool to stimulate growth in underdeveloped regions or to open new trade corridors. The lack of institutional coordination, the slow pace of regulatory reform, and inadequate human resource capacity further complicate the country’s ability to respond swiftly and effectively to global disruptions.

What can be done?

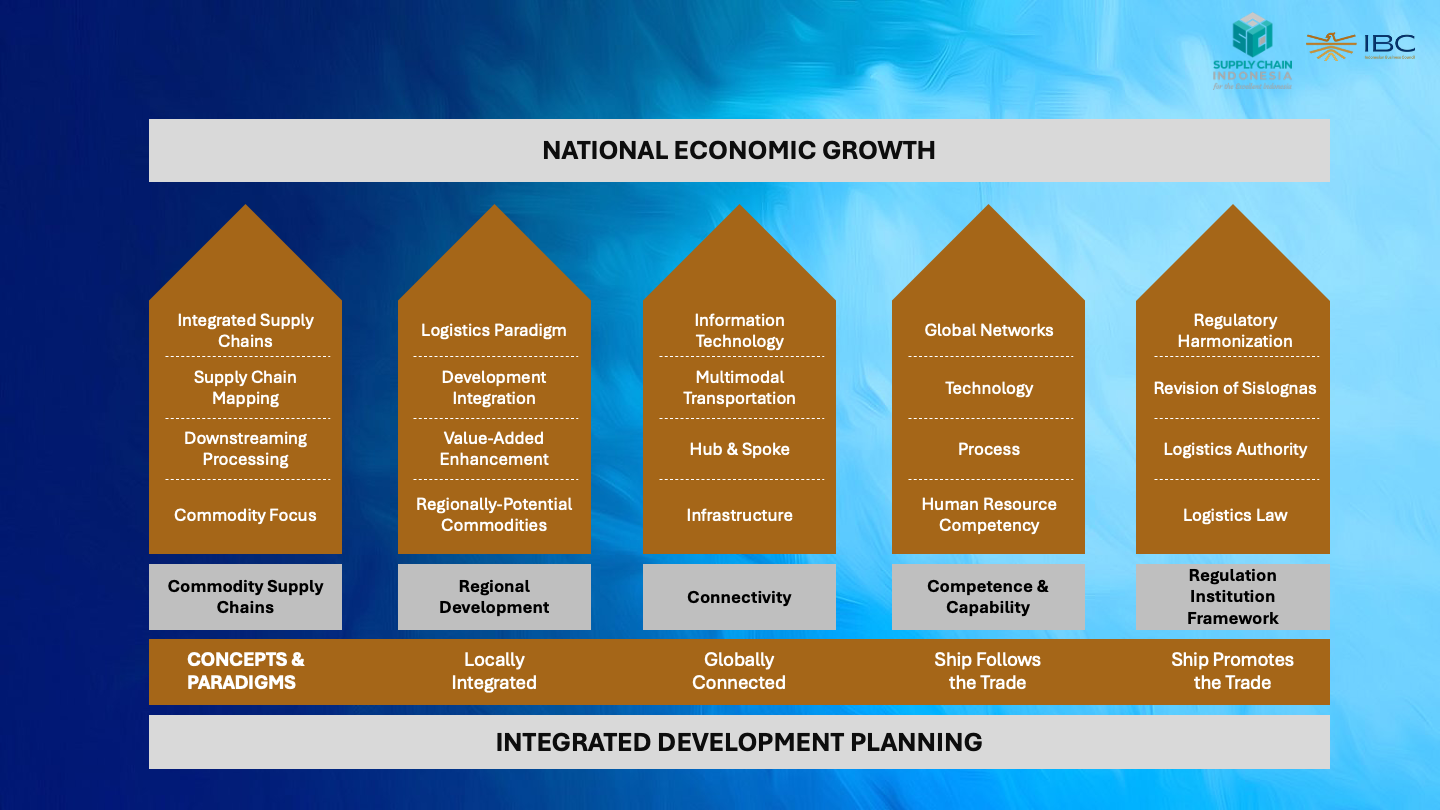

Source: Supply Chain Indonesia

To counteract global trade pressures and support its ambitious growth targets, Indonesia must build a robust and forward-looking logistics sector. These steps could include, but are not limited to:

1. Commodity Supply Chain Optimization

Focus on high-priority commodities and develop integrated, downstream-oriented supply chains. Mapping and coordinating these chains will ensure smooth, cost-efficient operations that add value and increase export readiness.

2. Regional Development Focus

Strengthen logistics capacity in high-potential regions through infrastructure investment and paradigm shifts—from reactive logistics planning to proactive, growth-driven logistics that stimulate new economic activities.

3. Connectivity Through Multimodal Integration

Develop and integrate transportation modes—including roads, ports, railways, and airports—into a unified system. Apply digital technology for route optimization, delivery tracking, and real-time visibility to reduce delays and improve efficiency.

4. Capability and Competency Enhancement

Invest in workforce development, leadership training, and technology adoption. Promote sustainable logistics practices like green transport, electric fleets, and emissions reduction to align with global standards.

5. Regulatory Reform and Institutional Strengthening

Accelerate the drafting of a Logistics Law to enhance legal clarity. Revise outdated regulations and establish a central logistics authority to ensure coordination, policy alignment, and swift implementation of national strategies.